We all remember the word problems from middle-school math:

If Jane can paint the fence in two hours, and Bill can paint it in three, how long would it take the two of them to paint the fence if they worked together?

Imagine that same word problem, except instead of painting a fence, Jane and Bill were software engineers.

If Jane can write 20 lines of code in one hour, and Bill can write it in two, how long would it take them to complete the task if they worked together … on one computer?

The scenario described above has a name. It’s called pair programming. And many engineers would have a NSFW answer to the question and tell you why pair programming is bad.

Pair programming, an idea that’s gained traction in recent years, tends to inspire strong opinions one way or another. Companies and organizations love it. Many engineers hate it. No matter which side you’re on, it’s not going away. But it is possible to make everyone happy with the right approach.

Pair Programming: Reasons to Hate It

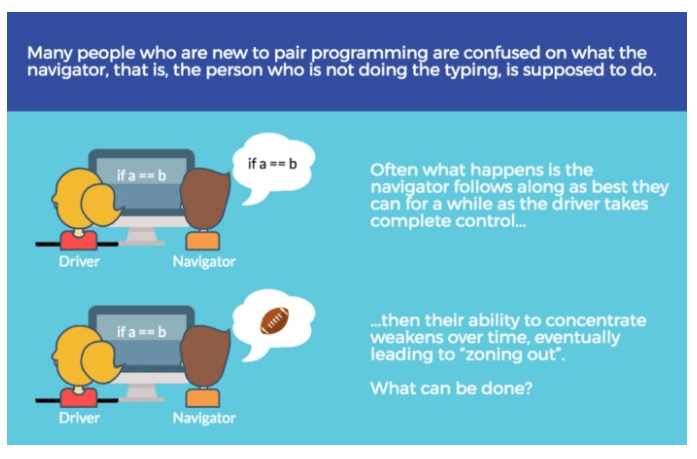

Before we go any further, a quick review for anyone who’s unfamiliar with the concept. Pair programming is a methodology in which two people work together on a single programming task. In most scenarios, the pair works on a single machine, with a “driver” and a navigator dividing tasks — entering code, observing to prevent bugs while discussing structure, style, and functionality.

(Source)

Companies that adopt pair programming have cited several benefits, including a shared project experience and ownership among developers, better understanding of project goals, effective collaboration, and happier employees. Some companies skip administrative processes like code reviews because the shared context is implicitly established and approved during the programming sessions.

A lot of people love pair programming and write emphatically about its benefits. But it’s not a universal love, as many engineers will tell you why pair programming is bad. Some will tell you they hate it.

Hate. It.

For a lot of engineers, programming is all about getting “into the flow.” It’s a euphoric state when everything is just coming together, and they’re able to work for hours on end, churning out high-quality code. Other developers see programming as a process of quiet reflection, trial and error, one-on-one with a problem, slowly building to a solution.

Pair programming interrupts that flow, or worse, prevents it from happening. It often follows a rigid schedule, dictating programming sessions at certain times, even if the developer isn’t in the right mindset. Some people simply work better on their own terms, when inspiration strikes.

On its face, pair programming is essentially two people doing one job. Some engineers say that only serves to destroy productivity, slowing the development process down. This can be especially harmful for startups that need speed above all else.

Another pair programming complaint is that it requires a rare, perfect match of two individuals. Such pairings are elusive because people are inherently different, with varying strengths and approaches to work that clash with others more often than not.

Finally, there’s the introversion problem. The introverted software engineer is a bit of a cliché, but there is some truth to it. As much as 40% of the population are introverts, and those people are drawn to jobs that involve independence, like programming.

For those people, working in pairs, talking to someone for six hours a day, can be mentally and physically taxing. For introverts, pair programming may be a “personal hell.” Research also suggests that the part of the brain used for speech is also used for programming. Engaging it constantly, switching between spoken language and coding language, can also be exhausting.

Pair Programming: Reasons to Love It

Despite the negative rep pair programming can have, there are some legitimate arguments to be made in favor of pair programming. It can make the code better, the employees happier, and the organizations more successful.

It may seem counterintuitive, but two people working on the same code can actually be more productive than if they worked separately. The productivity gains come not in the form of faster coding but by way of fewer errors and bugs, making review and refactoring faster or possibly redundant.

In addition, sometimes two people come up with better, more creative solutions by working together. By sharing ideas and discussing them out loud, pairs can get through obstacles and challenges quickly. A lone programmer can get stuck in a rut, stewing on a problem with no solution in sight, sapping productivity.

Interestingly, the productivity gains of pair programming continue when the two members are apart, working on their own between sessions. The energy and ideas generated during pair programming sessions have a lasting effect.

Pair programming also has some real upsides for employees, especially for junior-level developers. It encourages employees to share knowledge, so new hires and younger developers learn and grow their skills faster. This is immensely satisfying to junior developers whose confidence and passion for the work blossoms quickly. There’s a reciprocal benefit to senior developers, too, as their passion and focus get sharpened in the process.

Believe it or not, some developers find pair programming to be just plain fun. There’s a certain joy in working on a project as a team.

All of that adds up to some real tangible benefits for organizations. It results in faster, more efficient onboarding of new hires. It makes companies less reliant on individual “towers of knowledge,” and less vulnerable when they leave. It creates happier employees, who write better, cleaner code, resulting in better products and happier users.

From the organization’s standpoint, what’s not to love about pair programming?

Making Pair Programming Work

Pair programming doesn’t seem as if it will be going away anytime soon, and there are good reasons for your organization to implement it. But it’s not a plug-and-play solution, and you might face some resistance from developers telling you why pair programming is bad.

So here are some strategies you can use to make it work for your company and have your engineers enjoy it. Or at least tolerate it.

Understand it’s not one-size-fits-all

As good as it is, pair programming is not right for every task, every project, every time. It’s critical to know when to use it and when to go another way. That will depend on your organization, your people, and your projects.

You can start by trying pair programming on specific stories or tasks that would benefit from collaboration. If it touches a core feature, or presents a specific, difficult challenge, you might consider assigning it to a pair programming team. Conversely, tasks that are simple or time-sensitive might be best left to a solo programmer to just get it done.

However you implement it, be sure to let your teams evaluate the experience afterward to understand what worked, what didn’t, and why. Then, apply that knowledge the next time you consider pair programming.

Try different techniques

Pair programming isn’t just one thing. There are actually different types or versions of it, and the right for your organization, again, depends on your situation.

Truly collaborative pairing, like through CoScreen, allows you to have multiple drivers, and to switch between driver and navigator rapidly while letting users observe and continue doing other work on the side. Having the driver and navigator switch roles every so often can keep both engaged in the process. You can also use ping-pong pairing, in which the team follows a loop of writing, passing, and refactoring sections of code.

There are other techniques you can explore. The right technique depends on the task, but it might also be best left to the pair themselves to determine how they work best.

Follow general etiquette

The main thing to remember with pair programming, as with all personnel matters, is that you’re dealing with human beings. You should be sensitive to that, ensuring that the people you pair together won’t be at each other’s throats the first day.

Encourage pairs to be patient and empathetic toward each other. Create a dedicated area to document your company’s values, the purpose of pairing, and appeal to common courtesy. They should be open to trying one another’s ideas and able to explain and document their decisions. Be aware of your programmers’ personality types and how well they get along with others, and take that into consideration as you build your teams.

You can also pair people according to their seniority and experience to find the right fit for a project. Combining two senior programmers might be best for challenging, high-priority tasks, while a senior/junior combination helps with onboarding and development. Even junior/junior combinations can be beneficial in certain situations.

Finally, pair programming teams should use common sense to maintain effectiveness. Switching roles frequently and taking well-timed breaks helps keep them fresh and gives their mind a break.

Why Pair Programming Is Bad: It’s Best in Moderation

Pair programming can be an effective approach for your organization, even in an era of remote working. It will take some trial and error, and potentially overcoming time zone differences. But if you don’t overdo it, and you use it in the right situations for the right people and can get your teams to embrace it, you can make it work for, and provide benefits to your organization.

About the author:

Jason Thomas is the CTO and Co-founder of CoScreen, a radically different collaboration platform for engineering teams. He has worked in remote engineering teams for most of his careers with a focus on video conferencing applications.